Handcuffed workers are escorted into a bus for transportation to a processing center after an Aug. 7, 2019, raid by U.S. immigration officials at a Koch Foods Inc., plant in Morton, Miss. Immigration agents arrested 680 Latino workers in a massive workplace sting at seven Mississippi chicken processing plants in this operation during the first Trump administration. Scenes like this could be commonplace in the U.S. if former President Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for president, wins election next month and goes through with his promises to deport up to 15 million immigrants.

< 12px;">ELECTION 2024

< 12px;">Former President Donald Trump has pledged a nationwide purge and deportation of up to 15 million immigrants, creating a scenario unprecedented in American history. ¶ Trump’s advisers say it would entail creating detention camps and nationwide workplace raids. ¶ Critics fear that American citizens might be need to start carrying proof of citizenship with them at all times. . ¶ Observers anticipate the scale of the operation would compel the involvement of state, local and perhaps military forces, overwhelm already overtaxed courts, create tense international relations as the U.S. attempts to force other nations to accept the deportees, risk rounding up U.S. citizens, expose some refugees to immediate persecution in repressive states, harm businesses and propel the nation to places it’s never been.

< 12px;">Untangling the details of how this all would work is harrowing for immigration experts.

< 12px;">Trump’s plan — pegged by the American Immigration Council at an astounding $315 billion price tag — would inevitably include deporting law-abiding American citizens, and be disastrous for civil rights and the nation’s economy.

< 12px;">Michael Kagan, executive director of UNLV’s Immigration Clinic, says that would be a particular threat to Nevada.

< 12px;">There are nearly 190,000 undocumented immigrants in Nevada, 84% of whom have been in the United States for more than five years, according to Pew Research Center. About 1 in 10 Nevada households include an undocumented immigrant.

Trump has continued to make mass deportation a centerpiece of his campaign against the Democratic nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, ratcheting up his rhetoric by saying immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country,” echoing phrases used in 1930s Germany, and declaring, “We’re like a garbage can for the rest of the world.”

< 12px;">Nevada immigration advocates are issuing stern warnings about the “chaos” Trump’s proposal would create across the state.

< 12px;">“I dread it,” Kagan said. “I do not think people are as fearful of it as they should be because almost no one alive today has a memory of what a mass deportation campaign looks like.”

< 12px;">Expediting removal

< 12px;">Kagan figures a second Trump administration would need a “legal fig leaf” for a mass roundup campaign. That might be some-thing called “expedited removal.”

< 12px;">The process generally enables immigration officers to quickly deport people who they believe entered the country over the past 14 days if the person cannot prove they have been in the United States for two years.

< 12px;">However, no judge typically reviews the case. The same immigration officer questioning someone can issue a final ruling if the individual is not carrying documentation showing how long they’ve been in the country.

< 12px;">“That just means that an (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) officer ... can stop you and start questioning whether you have documentation to show that you’ve been present in the United States for at least two years,” said Cristian Gonzalez Perez, a fellow in the UNLV Immigration Clinic. “Not that many people have that.”

< 12px;">Trump’s mass deportation language largely focuses on people of Latino descent. It opens the door to racial profiling and forces the people concerned about being profiled to carry identification.

< 12px;">Currently, expedited removal only applies within 100 air miles of the United States’ borders (with Mexico and Canada), which does not include Nevada.

< 12px;">During Trump’s first term, the Department of Homeland Security published a notice expanding the policy to the entire country. However, court battles and the pandemic stifled the federal agency’s ability to institute the policy. Under President Joe Biden, the Department of Homeland Security officially rescinded its use of expedited removal outside of the 100-mile zone.

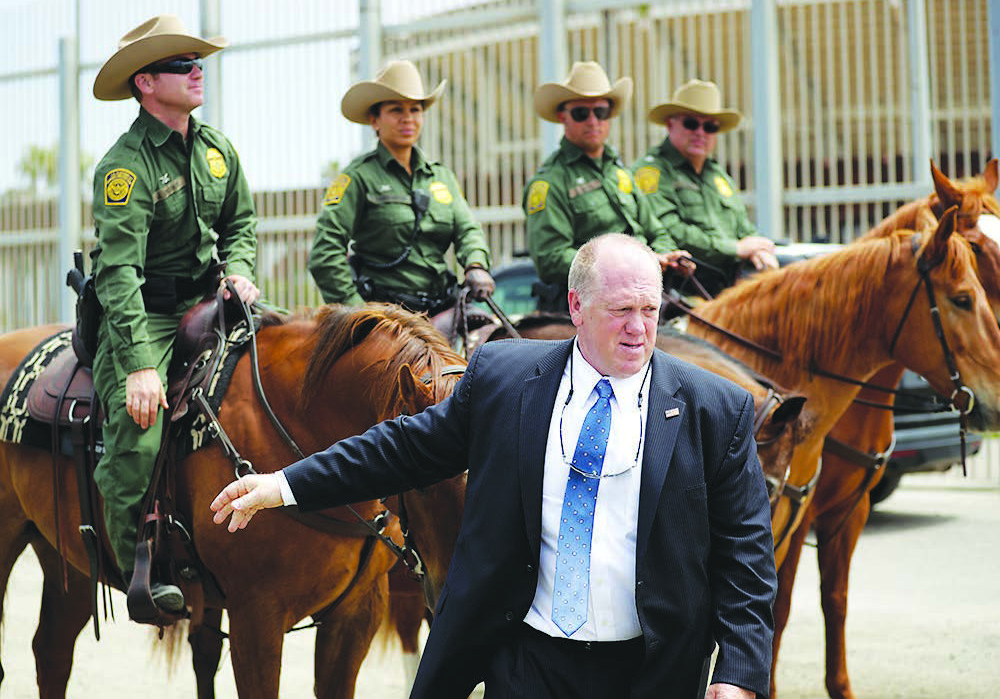

< 12px;">Trump earlier this month said that Tom Homan, who served his administration as acting director of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, would be “coming on board” if elected.

< 12px;">Homan is a contributor to Project 2025, ostensibly designed as a roadmap for a second Trump presidency that calls for expansion of expedited removal and a broad swath of immigration-related proposals.

< 12px;">Critics of Project 2025 say it’s an effort to install a white Christian nationalist theocracy in the United States, is marbled with racist policies and brimming with conspiracy theories with violent undertones.

< 12px;">“People need to be deported,” Homan told Time magazine. “No < 12px;" face="Arial">one should be off the table.”

< 12px;" face="Arial">< 12px;" face="Arial">Trump’s mass deportation language largely focuses on people of Latino descent. It opens the door to racial profiling and forces the people concerned about being profiled to carry identification.

< 12px;">Joint police-military operation

< 12px;">The courts system could be swamped, which critics worry could again turn into an excuse for skipping the courts.

< 12px;">During the 2020 fiscal year, 1.3 million immigration court cases were pending, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Now there are 3.7 million.

< 12px;">Hardeep Sull, an immigration lawyer in Las Vegas, said some of her cases are already going for another five or six years. The backlog, she believes, opens the door to ignoring typical processes.

< 12px;">Stephen Miller, Trump’s top immigration adviser, told The New York Times last year that the former president “will unleash the vast arsenal of federal powers to implement the most spectacular migration crackdown. The immigration legal activists won’t know what’s happening.”

< 12px;">The former president has suggested he would utilize the National Guard and local police along with current ICE and Border Patrol agents to carry out his mass deportation.

< 12px;">“It’s not going to be Trump himself riding in on a chariot collecting people,” said Laura Martin, executive director of the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada. “He’s going to need an infrastructure.”

< 12px;">Trump’s use of the National Guard stuck out to Kagan, who said the branch’s logistical abilities would be useful for transporting migrants and setting up detention camps to house them.

< 12px;">Miller told The New York Times that the administration plans to build “vast holding facilities that would function as staging centers,” potentially in Texas.

< 12px;">“Those are things that the Department of Homeland Security on its own would struggle to do,” Kagan said, “but with National Guard resources, they might be able to set up a much larger infrastructure that could actually carry out the kind of mass deportation they’re talking about.”

< 12px;">To get a sense of how many people would have to be in these “staging camps” and would require feeding, security, health care and child care for an indeterminate amount of time, consider this: In 2022 and 2023, the entire incarcerated population in the U.S. federal, state prisons and local jails is estimated to average between 1.5 million and 1.8 million, depending on the year. So what Trump and Miller are proposing is creating, staffing, funding and securing detention camps that could approach the size of all current U.S. incarcerations. And that doesn’t include the complicating issue of children in the camps.

< 12px;">Historically, rounding up more than 10 million people hasn’t be done one-by-one. It involves societal scale interventions and could include tactics that expose all citizens to scrutiny, targeting specific neighborhoods or sweeps of job sites where all employees are required to prove their citizenship status.

< 12px;">Local law enforcement, critics argue, is not set up to manage such duties and still keep their communities safe.

< 12px;">When Japanese Americans were detained in camps during World War II, there were full neighborhood sweeps by law enforcement and military.

< 12px;">The Nevada National Guard is under the direction of Gov. Joe Lombardo, a first-term Republican who leaned on a Trump endorsement in his 2022 election victory. His office did not respond to multiple requests for comment on his views on this.

< 12px;">Attorney General Aaron Ford, a Democrat, wrote in a statement to the Sun that he would not “dive deeply into legal hypotheticals,” but that his office would always “take a legal stand in defending the constitutional rights of Nevada residents.”

< 12px;">“As Nevadans and Americans, we should always strive to keep families together and avoid the ostracization of any Nevadans,” Ford wrote. “The Silver State protects its own.”

< 12px;">Martin said people in her organization, which includes member groups like the local ACLU and NAACP, were already having conversations about how to make sure Lombardo doesn’t follow through on Trump’s anticipated request for calling out the Nevada National Guard.

< 12px;">A deportation effort would also need the support of Metro Police to launch raids in the valley.

< 12px;">Metro in 2019 — when Trump was in office — ended its federal immigration enforcement 287(g) agreement. The controversial partnership called for holding detainees on misdemeanor charges until immigration agents could arrive and transfer to federal detention for removal from the country.

< 12px;">“We have to be realistic (about) the capacity of what we’re asking people to do. What kind of trauma would we be inflicting when, believe it or not, even families within law enforcement would be broken up,” Sull, the immigration lawyer, said. “It’s the unspoken truth in Nevada. We have mixed-status families so widely.”

< 12px;">Stressing families

< 12px;">Sitting in the conference room of UNLV’s Immigration Clinic, Gonzalez Perez is surrounded by dozens of painted handprints from children the center has helped stay in the United States.

< 12px;">Emigrating from Mexico with his parents in 2003, Gonzalez Perez is a Dreamer, one of the beneficiaries of the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which prevents some people who came to the United States at a young age from being deported.

< 12px;">For the past year, Gonzalez Perez has helped the unaccompanied children behind those handprints. But lately, when Gonzalez Perez has been reading over his cases, he’s been looking for ways to help his own family as well.

< 12px;">For anyone in the immigration community, elections are scary because policies might change for the worse. “There’s always that worry,” Gonzalez Perez said. “It used to be every four years, and then it changed to every two years, and now it seems like every single day where now you must start worrying, ‘OK. what’s going to happen depending on the election?’”

< 12px;">Gonzalez Perez remembers his father coming back home early because of workplace immigration raids. Under Trump’s mass deportation plan, he believes those raids would become more common. The stress it would create for undocumented immigrants is “unfathomable,” Gonzalez Perez said.

< 12px;">Martin said the process would be “complete chaos” with citizens being deported along with undocumented immigrants.

< 12px;">“If agents are encountering people in their communities and there isn’t (translation) available, it can very quickly become a situation where people aren’t able to literally communicate with the person detaining them, which can lead to mistakes,” said Kathleen Bush-Joseph, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute.

< 12px;">That situation also raises concerns about racial profiling, Bush-Joseph said.

< 12px;">“This is an attack on not just immigrants but people who you may assume are an immigrant,” Martin said. “I mean, I’m a Black person, and I know people can’t look at me and know where I was born or if I’m a U.S. citizen or not.”

< 12px;">Kagan said Trump’s ability to execute his plan would depend on the courts. Sull and Gonzalez Perez have mixed confidence in the system’s abilities.

< 12px;">“I like to always believe an officer of the court is an officer of the court, even when they get sworn into the judiciary,” Sull said, adding that courts had become increasingly politicized in recent years.

< 12px;">Fast-tracking processes

< 12px;">Project 2025 has specific recommendations to expedite expulsions, calling for significant changes to the Immigration Court system and deportation processes.

< 12px;">Those changes include: expanding expedited removal proceedings to their fullest extent under law; increasing the use of summary deportations and streamlining removal procedures; limiting asylum officers’ parole authority to only “urgent humanitarian reasons” or “significant public benefit;” and restricting immigration judges’ ability to administratively close cases or grant continuances.

< 12px;">< 12px;" face="Arial">It also calls for faster processing of deportation cases with less time for case preparation and limiting access to work permits during immigration proceedings.

< 12px;">To expedite case processing, it calls for reduced time between initial hearings and final decisions, creating performance metrics based on case completion speeds and prioritizing rapid processing of recent border crossers’ cases.

< 12px;">Although Trump did not move on mass deportation in his first term, some of his administration’s immigration policies were halted by courts.

< 12px;">When Trump tried to dismantle the DACA program protecting hundreds of thousands of Dreamers — people like Gonzalez Perez brought to the U.S. at a young age — the Supreme Court in 2020 blocked the plan despite its conservative majority.