Medical students help fill gap in health care system by matching in state

HIGHER EDUCATION

COURTESY PHOTOS

Touro University medical students found out where they would serve their residencies during a ceremony Friday, with many staying in state.

Touro University medical students found out where they would serve their residencies during a ceremony Friday, with many staying in state.

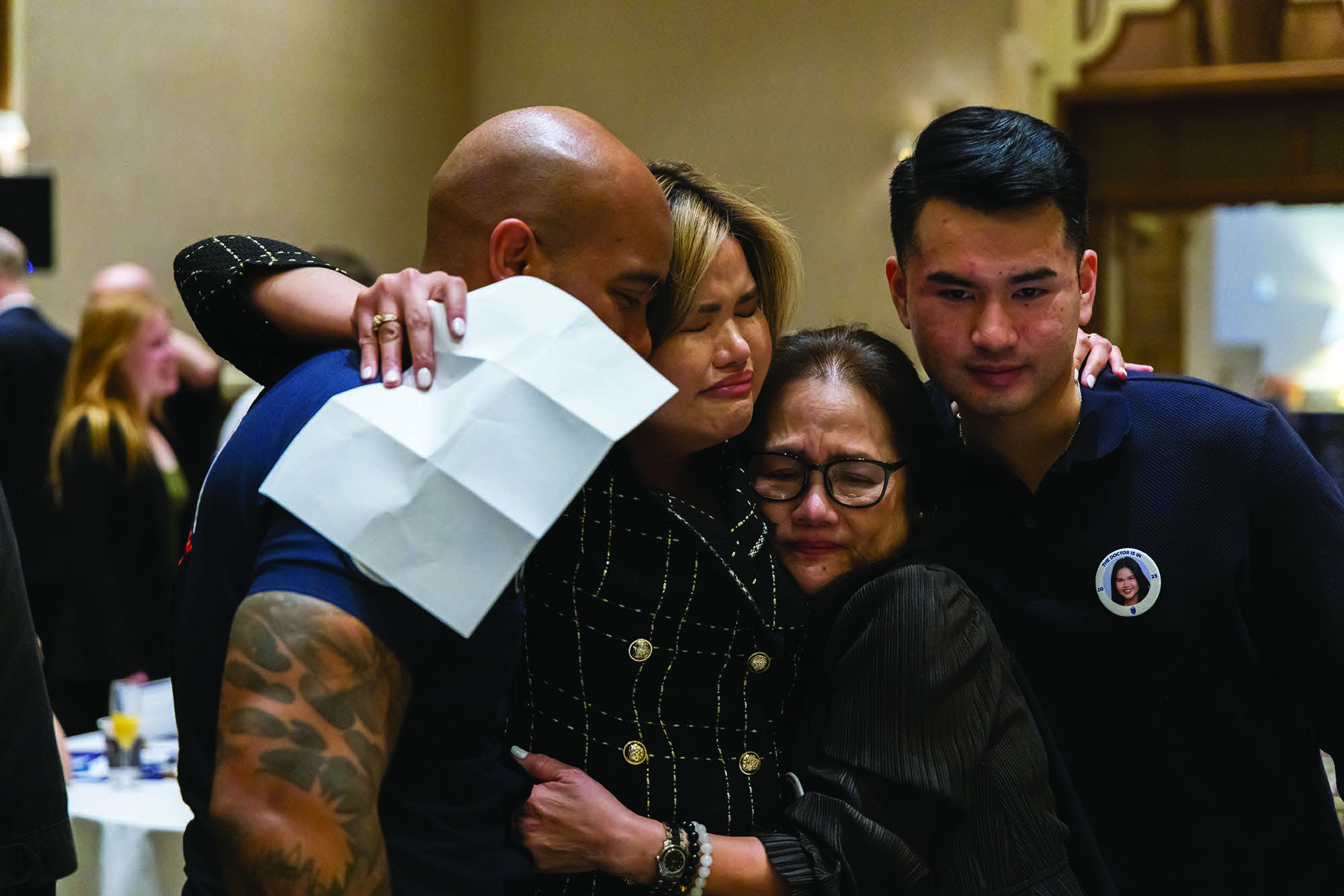

Family members support an emotional student who learns where she will serve her residency.

Touro University reported a record number of its osteopathic medical students will remain in Nevada for residencies, with 55 of 169 matched students staying in-state.

This helps address Nevada’s physician shortage, where all 17 counties lack sufficient primary care doctors, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration.

A 2023 study from the National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine said Nevada “faces a health care crisis” and needs an additional 2,561 physicians to meet the national standards.

Nevada averages one primary care physician per 1,760 residents; for Clark County, it’s one for every 1,830 residents.

“Part of the reason we are successful is because we have our mission in the right place,” said Dr. Wolfgang Gilliar, dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine at Touro University Nevada. “The medical school was founded on exactly that premise to help support the workforce in Nevada, because when the school was chosen for location, they knew there was not enough physician workforce, and we’ve consistently delivered and that’s part of what drives us.”

Medical students learn their residency placements on Match Day after a multi-month process.

Students first rank preferred specialties and hospitals, submit personal statements, academic records and board exam results.

Those advancing complete a secondary application detailing their aspirations and location preferences. Following interviews with program staff, both sides create rank lists that an algorithm processes to determine final matches.

The match celebration was Friday, with Touro University matching 168 of its 169 graduating students, Gilliar said.

UNLV’s Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine students also participated in Friday’s Match Day, with all 60 soon-to-graduate students securing residencies.

Forty-one percent will remain in Nevada for their specialty training, according to school officials.

Marc Khan, dean of the medical school, said that this was “the last big step prior to graduation” for these medical students, many of whom he has watched grow from when they first entered medical school.

“I’m going to be staying here; I’m joining the Southern Hills (Hospital and Medical Center) neurology department.

I’m super excited about that, to contribute back to where I’ve not only grown as a doctor, but grown up as a kid with physician parents in this city,” said Komal Sood, a medical student at UNLV. “I’m really excited to give back to this community.”

Nevada lawmakers have pushed bills at the state and federal levels to help bring more health care professionals to the region.

U.S. Sen. Jacky Rosen, D-Nev., recently reintroduced legislation allowing doctors and dentists in underserved areas to defer student loans interest-free until completing residencies. Meanwhile, 10 Nevada state senators are sponsoring Senate Bill 262, which would enable the Department of Health and Human Services to award grants for creating or expanding residency programs. At a March 13 Senate Committee on Health and Human Services meeting, Kahn noted that Nevada must either “import more, or grow our own” physicians.

Medicare capped graduate medical education positions by state in 1997, giving Nevada only 403 positions compared with California’s more than 9,000.

Local hospitals are limited in how many trainees they can bring on board, said Jeff Moroski, chief medical officer for HCA Healthcare’s Far West Division, which includes institutions like Sunrise, Sunrise Children’s, MountainView and Southern Hills Hospitals. For example, Sunrise Hospital has over 800 patients in it, but a residency cap of only 19 people.

There’s also a lack of diverse residencies, Gilliar said.

Some students — including one who participated in Match Day on Friday — have to go out of state to study certain fields because Nevada has no residencies or very few spots. For example, there’s no dermatology position, and very few for those specializing in nose and throat medicine, Gilliar said.

About 40% of graduates from a Nevada medical school and around 60% of those with medical residencies in Nevada practice here, Kahn explained.

When a person graduates from a Nevada medical school and completes an in-state residency, that retainment increases to 80%, which is “critical to providing the health care future for our state.”

“(Graduate medical education) is an important and critical component of the services we provide in our hospitals,”

Moroski said. “There are things we need to do to proactively raise that number.

We’ve been able to keep our graduates at the same rates that were mentioned before in the state, and we think that’s why this bill is such a great commitment to raise that number of trainees. All these issues are important to help us achieve the goal of really serving Nevadans.” grace.darocha@gmgvegas.com / 702- 948-7854 / @gracedarocha

This helps address Nevada’s physician shortage, where all 17 counties lack sufficient primary care doctors, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration.

A 2023 study from the National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine said Nevada “faces a health care crisis” and needs an additional 2,561 physicians to meet the national standards.

Nevada averages one primary care physician per 1,760 residents; for Clark County, it’s one for every 1,830 residents.

“Part of the reason we are successful is because we have our mission in the right place,” said Dr. Wolfgang Gilliar, dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine at Touro University Nevada. “The medical school was founded on exactly that premise to help support the workforce in Nevada, because when the school was chosen for location, they knew there was not enough physician workforce, and we’ve consistently delivered and that’s part of what drives us.”

Medical students learn their residency placements on Match Day after a multi-month process.

Students first rank preferred specialties and hospitals, submit personal statements, academic records and board exam results.

Those advancing complete a secondary application detailing their aspirations and location preferences. Following interviews with program staff, both sides create rank lists that an algorithm processes to determine final matches.

The match celebration was Friday, with Touro University matching 168 of its 169 graduating students, Gilliar said.

UNLV’s Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine students also participated in Friday’s Match Day, with all 60 soon-to-graduate students securing residencies.

Forty-one percent will remain in Nevada for their specialty training, according to school officials.

Marc Khan, dean of the medical school, said that this was “the last big step prior to graduation” for these medical students, many of whom he has watched grow from when they first entered medical school.

“I’m going to be staying here; I’m joining the Southern Hills (Hospital and Medical Center) neurology department.

I’m super excited about that, to contribute back to where I’ve not only grown as a doctor, but grown up as a kid with physician parents in this city,” said Komal Sood, a medical student at UNLV. “I’m really excited to give back to this community.”

Nevada lawmakers have pushed bills at the state and federal levels to help bring more health care professionals to the region.

U.S. Sen. Jacky Rosen, D-Nev., recently reintroduced legislation allowing doctors and dentists in underserved areas to defer student loans interest-free until completing residencies. Meanwhile, 10 Nevada state senators are sponsoring Senate Bill 262, which would enable the Department of Health and Human Services to award grants for creating or expanding residency programs. At a March 13 Senate Committee on Health and Human Services meeting, Kahn noted that Nevada must either “import more, or grow our own” physicians.

Medicare capped graduate medical education positions by state in 1997, giving Nevada only 403 positions compared with California’s more than 9,000.

Local hospitals are limited in how many trainees they can bring on board, said Jeff Moroski, chief medical officer for HCA Healthcare’s Far West Division, which includes institutions like Sunrise, Sunrise Children’s, MountainView and Southern Hills Hospitals. For example, Sunrise Hospital has over 800 patients in it, but a residency cap of only 19 people.

There’s also a lack of diverse residencies, Gilliar said.

Some students — including one who participated in Match Day on Friday — have to go out of state to study certain fields because Nevada has no residencies or very few spots. For example, there’s no dermatology position, and very few for those specializing in nose and throat medicine, Gilliar said.

About 40% of graduates from a Nevada medical school and around 60% of those with medical residencies in Nevada practice here, Kahn explained.

When a person graduates from a Nevada medical school and completes an in-state residency, that retainment increases to 80%, which is “critical to providing the health care future for our state.”

“(Graduate medical education) is an important and critical component of the services we provide in our hospitals,”

Moroski said. “There are things we need to do to proactively raise that number.

We’ve been able to keep our graduates at the same rates that were mentioned before in the state, and we think that’s why this bill is such a great commitment to raise that number of trainees. All these issues are important to help us achieve the goal of really serving Nevadans.” grace.darocha@gmgvegas.com / 702- 948-7854 / @gracedarocha