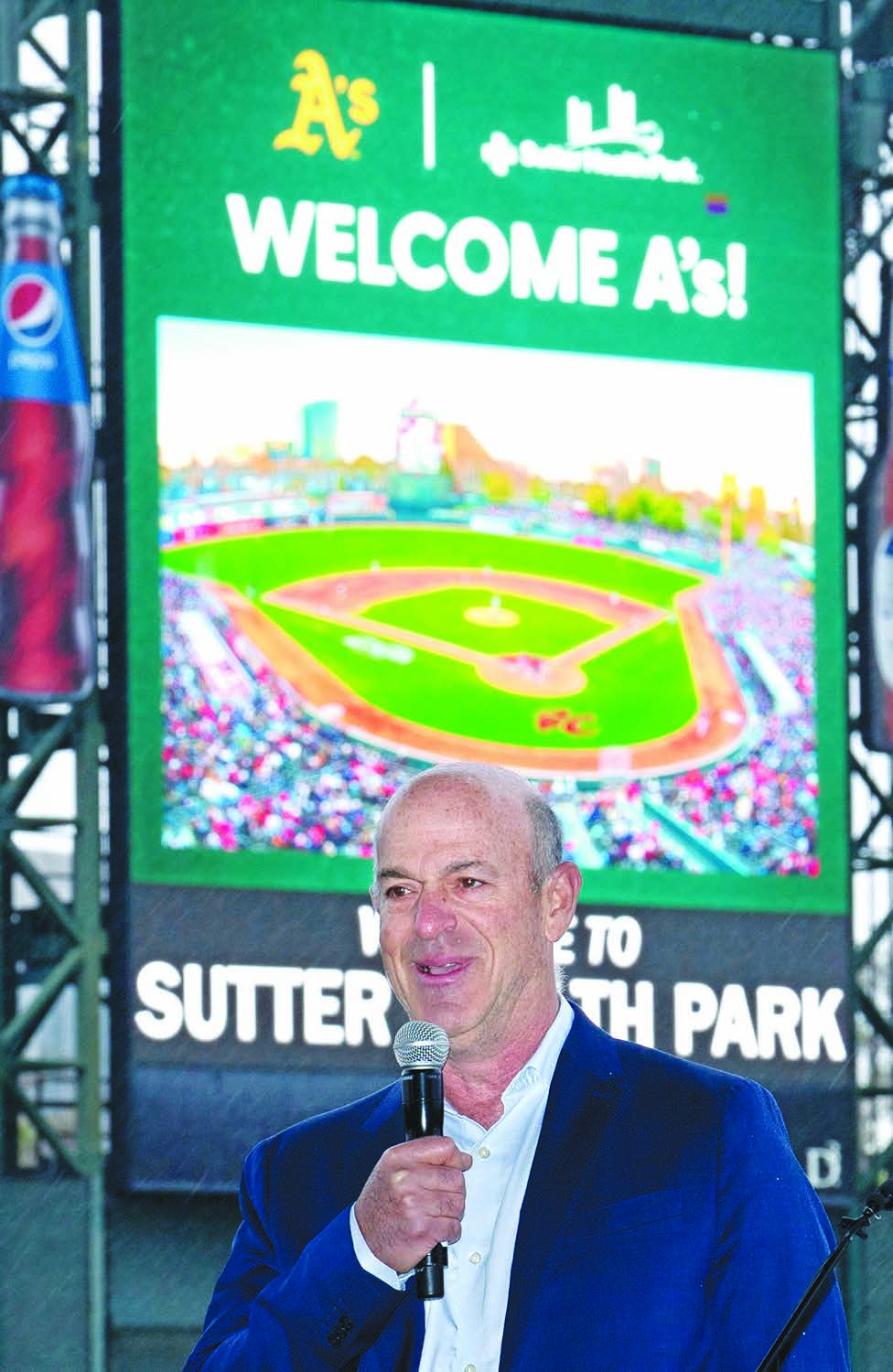

John Fisher, owner of the Athletics baseball team, announces April 4, 2024, that his team would leave Oakland after the 2024 season and play temporarily at a minor league park.

The A’s announced the decision to play at the home of the Sacramento River Cats from 2025-27 with an option for 2028 after being unable to reach an agreement to extend their lease in Oakland during that time.

Starting today, thousands of people will pack into Sutter Health Park on A’s game days, funneling new dollars into city coffers and local businesses.

Small-business owners are making improvements in preparation for fans’ arrival. Businesses are applying for permits near the ballpark, and vacant groundfloor retail spaces are receiving new attention, said Traci Michel, West Sacramento’s director of economic development and housing. The city expects in-stadium spending alone will boost sales tax revenues.

The team’s three-year tenure at West Sacramento’s minor league stadium will bring new attention to a city that the region’s locals have long regarded with expectations of growth. Over the past 30 years, business owners have bought restaurants, scooped up plots of land and built apartment complexes on the belief that West Sacramento is poised for more investment.

“We feel like we got in on the ground level,” said Clay Nutting, co-owner of Franquette, a wine bar and café that opened three years ago in West Sacramento.

Though the team plans to relocate to Las Vegas in 2028, civic leaders are mindful that the city will be in the national spotlight until then. Their goal, said Mayor Martha Guerrero, is to keep fans in town after games and show the region what West Sacramento has to offer.

Long considered an industrial town, West Sacramento was already growing steadily before the arrival of Major League Baseball. In 2023, the city’s population was 55,842 — up nearly 88% since 1990.

Sacramento’s population, by comparison, has grown 41% in the same time.

“West Sacramento is changing every day. There’s new stuff going up all over,” said Jerry Shockley, a retired roofer who has lived in the city for 34 years. “Everybody knows it’s going to grow.”

Some business and government leaders believe the team’s presence will lend an additional boost. And they believe they can turn the three-year stint into longterm momentum.

“It does give us an opportunity to step onto this national stage,” Michel said. “We know it will increase exposure for our riverfront, for the Bridge District, for our amazing local restaurants and entertainment venues.”

Stadiums and psychology

West Sacramento was once thought of as a rough-and-tumble industrial outpost, home to factories that were unwanted in other parts of Yolo County. It had a reputation for illicit entertainment that stretched back to the speakeasies and saloons of the Gold Rush era.

In 1986, eager to gain more control over the area’s destiny and tax dollars, residents voted to incorporate. They united an area of about 25,000 people in four hamlets — West Sacramento, Broderick, Bryte and Southport — into a new city.

In the city’s early years, leaders worked hard to set the conditions for long-term economic prosperity, said state Sen.

Christopher Cabaldon, who served terms as West Sacramento’s mayor between 1998 and 2020. But they first had to sort through the fundamental challenges that resulted from about 100 years with little investment.

“While everybody was waiting for retail, and waterfront services, and a downtown, and entertainment, the city was really just trying to make sure: ‘Do we have an adequate water supply?’ ” he said.

“There was definitely a lot of pent-up energy and hope.”

Some people, he said, grew skeptical that West Sacramento would achieve the kind of growth that its civic leaders dreamed of.

“When you have potential for 100 years, that potential starts to become disabling,” Cabaldon said. “When folks would have an interesting idea, or somebody wanted to try what might be a cool project or a new amenity, some people would get excited, and others would say, ‘Ah, I’ve seen that before. That’ll never happen.’ ”

In the 1990s, a group led by a former San Jose Sharks president began rounding up financing to build a minor league stadium in West Sacramento, with aspirations to bring professional baseball back to the region after a 25-year drought.

When it opened, the ballpark — then known as Raley Field — was one of the most expensive minor league stadiums in the country. A little more than 14,000 fans showed up to the first game on a cold, drizzly Monday night in May of 2000 — more than double the crowd watching the A’s game at the Coliseum that evening, the Bee reported at the time.

Cabaldon said it felt like a breakthrough for the city, psychologically. People began to think differently about what might be possible.

“Suddenly people’s eyes were on West Sacramento,” Cabaldon said. “The direct economic impact of the ballpark in those early years wasn’t enormous. It wasn’t any better than having a supermarket on the same location in terms of tax revenue or jobs or anything like that. But it really did change the psychology and the investment climate — and the sense that we could do something big.”

After that, the city won a global competition for an IKEA. It removed a rail line that had blocked the waterfront, and built out a network of bike lanes. It created a slew of educational programs, like college savings accounts for kindergartners and paid internships for high schoolers, Cabaldon said.

In the early 2000s, the city caught the eye of developer Mark Friedman.

Friedman’s firm, Fulcrum Property, started buying land in West Sacramento in 2004. At the time, he said, the area was full of industrial warehouses, many of which couldn’t be saved or converted.

“We really had to start from scratch,” he said. “It created this incredible blank canvas.”

Soon his mixed-use development, Pierside, will add 260 apartments to West Sacramento’s Bridge District. Friedman said he expects the first portion of the project to be finished in March of 2026.

“It is within a mile of some of the best amenities in our community. The Golden 1 Center. Sutter Health Park. The Crocker Art Museum. The train museum. The science museum. The Capitol. All within a mile of our site,” Friedman said. “When you look at an aerial, you see this incredible stretch of riverfront — immediately opposite the downtown — that was significantly underdeveloped. It was just warehouses.

So I knew that there was a great opportunity.”

Today pockets of retail are interspersed with new apartment complexes, riverfront parks and single-family homes. Downtown Sacramento is steps away. Still, the cities are divided by a river, an interstate and a county line.

Cabaldon acknowledged that these days the city resists easy definitions.

“It doesn’t really fit in a box any longer.

It is rural, it’s suburban, it’s hip urban. It’s also older urban. It’s industrial, it’s historic, it’s ethnic enclaves,” Cabaldon said.

“It’s so many different things that make it sort of defy easy characterization as a bedroom community or something. … Maybe because it came from these four different hamlets. Maybe just because it didn’t have control of its destiny, so it was kind of whatever other people wanted to make it for a long period of time, and also because it is one of the oldest places in the region. It defies a unitary concept.”

Friedman called it “the best of both worlds.”

“You can easily go to the party,” he said.

“But you can also quickly go home and get a good night’s sleep.”

Just as ‘sizzling’ Ernesto Delgado is hopeful that on game days, baseball fans will wander along the city’s waterfront, or across Tower Bridge to visit the railroad museum in Old Sacramento. They might find their way to his restaurant, Sal’s Tacos, or to those of his peers: The Tree House Cafe on Third Street, or Franquette on Bridge Street.

“The revenue that it’s going to generate, from parking to dining — to new business opportunities that are going to generate tax revenue for the city — I mean, right? It just goes, goes, goes and goes,” said Delgado, who chairs the West Sacramento Chamber of Commerce and owns the Sacramento restaurants Mayahuel, Octopus Baja and La Cosecha, among others.

Delgado said he planned to add a “salon de fiesta” on the back side of his West Sacramento restaurant, where people can watch the A’s games on televisions and enjoy a buffet-style meal for a flat price.

Sal’s Tacos gets busier on days when the minor league team, the River Cats, plays at Sutter Health Park, he said. When a major league team moves in down the road, Delgado wondered, will business double, triple or even quadruple? On a recent morning, a concrete truck churned outside the stadium, and a group of construction workers toiled away on a sidewalk repair. To the southeast and north of the park, apartment complexes advertised available units.

A passerby wondered aloud if the stadium would be ready in time for opening day, mere weeks away. To the east, the skyline of downtown Sacramento framed Tower Bridge.

A few blocks down at the Tree House Cafe, less than a quarter-mile from the stadium, owner Jeff “Fro” Davis said he secured a liquor license and planned to put in a full bar and snack shed.

Davis aims to offer live music to draw in fans from the ballpark, “bringing them over like the Pied Piper.” When the Athletics take the field at Sutter Health Park, his café is well-situated to become a pregame hangout spot on weekdays, and a post-game hangout spot on weekends. He wants to become part of the ritual for fans from out-of-town, and intends to make sure they leave knowing that West Sacramento is “just as ‘sizzling’ as the other side of the river.”

In his view, what was once a sleepy, blue-collar village is becoming an extension of downtown Sacramento.

“I think people are going to get rid of the word ‘West,’ ” Davis said.

Long-term MLB?

Some West Sacramentans are hopeful that the A’s could remain in the region beyond the expected three years.

“The first attraction in Las Vegas is shows and food, followed by Raiders games,” Davis said. “When you look at the fan base we already have here, versus Vegas, where baseball would be, what, the sixth attraction?”

The A’s declined to provide an interview.

The team has signaled its commitment to the move, and earlier this month announced players would wear a Las Vegas patch while playing in West Sacramento.

“We’re going to be doing things throughout the next three years that remind everybody, on a continual basis, that Las Vegas is our home, and that we will be here shortly,” A’s owner John Fisher said during a news conference there announcing the patch.

Some residents and officials have their hearts set on another oft-discussed possibility: That the region would be selected as a home for an MLB expansion team.

The idea gained new relevance earlier this year when Kings owner Vivek Ranadivé pitched MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred on the Sacramento region during a visit here, as the Bee previously reported.

“This is a great opportunity for the region to audition,” said Cabaldon, the former mayor. There is land available near the stadium, he said, which leaves plenty of opportunities open.

But first, he said, the key will be to enjoy the team while it is here, without obsessing about the future.

As for the city, many pointed out that it was already growing before Major League Baseball’s arrival.

“West Sacramento, it’s been on this path since I’ve been here,” said Delgado, the restaurant owner. “Like anything, it seems like it takes a long time. But it’s actually happening pretty fast.”

What is certain, officials said, is that a major league team’s presence will bring new attention to the city.

“What’s exciting about the A’s coming is, it gives people an opportunity to see what we’re up to, and to see what the view looks like on that side of the river,” Friedman said. “And it’s pretty good.”